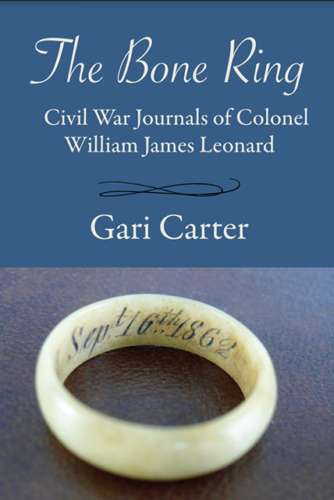

When Colonel William Leonard died in 1901, among his effects was found a lovely jewelry box containing a simple ring carved of cow bone and engraved with his birthdate and the year of his imprisonment during the Civil War. This humble memento, so carefully preserved, was made for him by his men to mark his 46th birthday when they were all prisoners of war in the Confederate Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia.

Also found was his journal, which begins when he was colonel in Purnell’s Legion Infantry and charged with protecting telegraph and rail lines in Maryland and Virginia, and ends after he was paroled from Libby Prison and returned to Maryland.

The bone ring and journal writings were passed down through his descendants, and his memory has been kept alive through family stories. Leonard’s great-granddaughter Gari Carter who now presents Col. Leonard’s journal, richly annotated and supplemented with family lore and local history.

Book Information

100 pp, 21 B&W images, 2 maps

Print ISBN: 978-1-955068-05-5

Price: $14.95

eBook ISBN: 978-1-955068-06-2

Price: $8.99

Available through Amazon, IngramSpark and all major distributors.

ca. 1855-1862(?)

Advance Praise for The Bone Ring

“This Civil War diary of a Union officer from Maryland’s Eastern Shore who was captured during the Second Bull Run campaign offers informative glimpses of life in Richmond’s Libby Prison and the resilience of a 46 year-old soldier whose patriotic convictions helped him survive the ordeal. A delightful bonus of the volume is the poetry composed by Colonel Leonard and inserted as part of his journal.”

James M. McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era

“William James Leonard forsook the comforts of home and family to serve his country in the Civil War. In doing so, he suffered physically and mentally, especially during his time as a prisoner of war. Yet even returning to civilian life, he aided in subduing rebel activities on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. His story deserves to be told.”

Dr. Thomas G. Clemens, editor of The Maryland Campaign of 1862

Press and Reviews

“Maryland’s role in the Civil War has received increased scholarly attention over the last dozen or so years. Works on a variety of Old Line State Civil War topics have only deepened a pool of significant past studies on the state’s major military actions, its divided civilian population, the institution of slavery, and the process of emancipation. To help craft these studies, historians have drawn upon an assortment of published and unpublished primary sources to provide examples and serve and the evidence for the conclusions they offer.

Adding to the relatively small body of published primary sources that cover the experiences of Maryland’s Federal soldiers is The Bone Ring: Civil War Journals of Colonel William James Leonard, edited by Leonard’s great-granddaughter Gari Carter. This slim volume only covers a little more than a month’s timeframe, but those five weeks, as the state’s immediate future hung in the balance, also proved to be some of the most eventful of Leonard’s lifetime.

William James Leonard was 45-years-old when he became the colonel of the Purnell Legion Infantry. Born and raised on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Leonard farmed, served in the state legislature, and ran a business before the Civil War. Like many of his neighbors, Leonard had enslaved men, women, and children, but apparently manumitted them in the years preceding the war. However, unlike many of his neighbors, Leonard was a committed unionist. While political issues such as Federal troop movements through Maryland, and whether the state would secede or remain loyal to the United States led to violence and uncertainty, Leonard maintained steadfast in his belief in a perpetual and indivisible Union.

The Purnell Legion, named for its founder, William H. Purnell, once the Maryland state comptroller, and then the postmaster of Baltimore, originally consisted of nine companies of infantry, two companies of cavalry, and two batteries of artillery. When Col. Purnell resigned in February 1862, the three branches of service became independent and Leonard became colonel of the infantry.

Serving first along Virginia’s Eastern Shore before receiving a transfer to the Shenandoah Valley for service at Harpers Ferry, and then becoming part of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia, Leonard and Purnell’s Legion was at Catlett’s Station in Fauquier County along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad when disaster struck. Leonard began recording events in his journal on August 20, 1862.

While suffering from a bilious fever, and after taking quarters at a local citizen’s house who had requested a guard to ensure the safety of his property, Leonard was captured on August 22. Gobbled up by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry, Leonard described his predicament: “I had nothing to do but submit, being entirely unarmed and . . . surrounded by soldiers.” (19) At first promised a parole, but then informed that he would not, Leonard and others taken prisoner moved to Warrenton where they stayed a couple of days, then moved on the Culpeper.

Leonard’s journal, although rather brief, does provide some excellent documentation on the movement and treatment of the Catlett’s Station prisoners. Leonard describes different aspects of the trip from Catlett’s to Richmond, including providing commentary on weather conditions, descriptions of landscapes (including the Cedar Mountain battlefield), food the prisoners were offered, and some friends and enemies he encountered along the way.

Arriving at Libby Prison in Richmond on August 28, Leonard and his comrades made do as best they could. Leonard passed a difficult first night in captivity on “two rough benches which kept me off the filthy floor.” (25) Apparently unaccustomed to duties like laundry and cooking, which were probably provided by African American camp servants before his capture, now Leonard had to perform those tasks himself. His recorded accounts have excellent descriptions of his prison experience.

Leonard’s incarceration proved rather short compared others later in the war when the prisoner exchange system broke down. Leaving Libby on September 24, less than a month after arriving, he was obviously relieved, “Our doors are open, thank God,” he wrote. (40) A memento Leonard kept of his prison time was a finger ring carved from a beef bone by his imprisoned friends. Traveling by boat down the James River to Fort Monroe, then up the Chesapeake Bay to Annapolis, Leonard’s journal ends on September 27, 1862.

Editor Gari Carter provides a beneficial epilogue that details Leonard’s life following his imprisonment and then the resignation of his command of the Purnell Legion in November 1862. In addition to the fine footnoting Carter provides, there are extras provided in the book including some of Leonard’s poetry and the family’s genealogy.

The Bone Ring makes fine addition to the few published primary accounts of Federal Marylanders. Its details of military capture, transportation, and incarceration are sure to of value to researchers seeking examples of these soldier experiences.”

– Tim Talbot, Emerging Civil War, Nov. 2, 2023

Civil War Books and Authors

This book’s title refers to one example among many types of war art produced by soldiers throughout the history of warfare, particularly by those with a lot of free time on their hands but little in the way of traditional art-making supplies. Common examples include the celebrated trench art of WW1 and the artistic renderings of American Civil War POWs, this remembrance ring, of course, being among the latter. From the description: “When Colonel William Leonard died in 1901, among his effects was found a lovely jewelry box containing a simple ring carved of cow bone and engraved with his birthdate and the year of his imprisonment in Libby Prison. This humble memento, so carefully preserved, was made for him by his men to mark his 46th birthday when they were all prisoners of war in the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia.“

Preserved along with that cherished ring was Leonard’s wartime journal, “which begins when he was colonel in Purnell’s Legion Infantry, which was charged with protecting telegraph and rail lines in Maryland and Virginia, and ends after he was paroled from Libby Prison and returned to Maryland.” Now his great-granddaughter, Gari Carter, “presents Col. Leonard’s journal, richly annotated and supplemented with family lore and local history.”

The resulting publication, The Bone Ring: Civil War Journals of Colonel William James Leonard, supplements the journal with an introduction (which includes a summary of Leonard’s pre-Civil War life as well as a capsule history of the Purnell Legion), an epilogue describing the Colonel’s service after his release from Libby Prison as well as his postwar life, and some Leonard family genealogy. The text is also extensively footnoted by Carter.

Leonard and his men participated in the Eastern Shore expedition of 1861, and his command also served in Baltimore, the Lower Shenandoah Valley, and northern Virginia. Essentially a record of Leonard’s POW experience, the journals (dated August 20, 1862 through September 28, 1862) transcribed in the book “begin when he was serving on guard duty for the Orange & Alexandria rail lines from Catlett’s Station to Culpeper Court House, Virginia” (pg. 10), mere days before he was captured and sent to Richmond. They end with his return to Union lines upon release from Libby Prison.

With so many individual Civil War stories lost to history, Leonard is fortunate in having a caring, and capable, custodian of his memory in descendant Gari Carter, who has also published the Civil War journals of another ancestor (see her 2008 book Troubled State: Civil War Journals of Franklin Archibald Dick.

The Laurel of Asheville

Black Mountain author Gari Carter mined her family’s rich past for her latest book, The Bone Ring. Through journal entries, the book—annotated and supplemented with family lore and local history—tells the story of Carter’s great-grandfather Col. William Leonard’s time as a Civil War prisoner. “My family always told our stories, and it was the children’s job to remember and pass it on to the next generation,” Carter says. “For The Bone Ring and Troubled State [about her great-great-grandfather], I spent years researching history, localities, family tales and general background.”

An unexpected birthday present in difficult times gave the book its title and cover image. “While in Libby Prison in Richmond, VA, the men were given parts of cattle to eat, which they had to cook themselves in the basement of the old tobacco warehouse,” Carter says. “Col. Leonard’s men secretly carved the ring from the leftover cow bones and engraved the date of his 46th birthday, rubbing ashes from the fire into the letters to make them stand out. They gave it to him as his only birthday present that year.” The ring was found among his belongings when he died in 1901.

“There are many things that concern us in today’s world, and it can seem overwhelming,” Carter says. “My books carry a lot of personal history and emotions, making them deeply relatable and meaningful to readers.”

The Midwest Book Review

“The Bone Ring: Civil War Journals of Colonel William James Leonard is a fascinating and informative American Civil War memoir that is informatively enhanced for the reader with the inclusion of a number of maps, black/white illustrations, a ten page family genealogy, and a ten page bibliography. It should be noted for the personal reading lists of students, academia, civil war historians, and non-specialist general readers with an interest in the subject that The Bone Ring is also available in a digital book format (Kindle, $8.99).”

The Mountain Xpress, Asheville, NC

Local author Gari Carter grew up listening to family stories about relatives who served in the Civil War, expecting to pass them along to future generations. She shares the story of her great-grandfather in her new book, The Bone Ring: Civil War Journals of Colonel William James Leonard, which is based on writings handed down by Leonard.

Leonard served as colonel in Purnell Legion Infantry in Maryland. When he died in 1901, he left behind a journal and a jewelry box containing a ring engraved with his birth date and the year of his imprisonment during the Civil War. The ring was a birthday present made out of cow bones left over from food served to members of his infantry while they were all prisoners of war at Libby Prison in Richmond, Va. The men engraved the colonel’s birth date into the ring and rubbed it with ashes to make the letters stand out.

Both the ring and journal were passed down through Leonard’s descendants and eventually reached Carter, who had previously published the Civil War journals of another ancestor.

“My new book is from another branch of my family, with a firsthand account of life in a Civil War prison,” says Carter. “For someone with a family member or friend incarcerated, it would give hope. It is inspiring in today’s world to read of someone overcoming a dreadful experience, even in the 1860s compared to now.”

Carter came to Asheville in 1993 on a book tour with her first book, Healing Myself. She says she fell in love with the area and moved to Black Mountain, where she still resides.

– Andy Hall

The Sarasota Herald Tribune

“Finding connection: Letters and digital records reconnect people to their roots and others” by Emily Leinfuss Special to the Herald-Tribune | USA TODAY NETWORK (excerpt)

When it comes to the Civil War, Gari Carter has more than one story to tell. “Both my maternal ancestors fought for the Union, Franklin Dick in St. Louis, and Colonel William James Leonard from Maryland to Virginia,” said the Sarasota author.

Civil War diaries

Carter wrote about the former in her 2008 book “Troubled State: The Civil War Journals of Franklin Archibald Dick.” Her book about Colonel Leonard, “The Bone Ring,” will be published this year. It was named for a family heirloom: the ring that Col. Leonard’s men carved him for his birthday from the leftover bones of their food, said Carter.

Despite having diaries from both men, each book took years of investigation. “There is personal satisfaction in pulling together all the research about Franklin Dick and Colonel Leonard,” said Carter. A highlight along the way was a “visit to my 99-year-old cousin who had the bone ring and hearing his memories,” she said.

“It feels as if I am honoring my ancestors in ways that would have made them happy,” she added.

Carter admits that Internet resources are increasingly helpful when investigating family history. But there’s nothing like being able to see and touch original documents and photographs. That’s also the opinion of Phaedra Dolan, director of Historical Records for the Manatee Clerk. Her department operates two historical villages, two museums and extensive records archives that are housed in Bradenton’s historic Carnegie Library.